Ernest Bristow Farrar - a biography

by Robert Weedon

Ernest Bristow Farrar was born in Lewisham, London in July 1885, but moved in 1887 to Micklefield in Yorkshire, where his father was a clergyman.

The rest of his life was very much centred in the North of England, which had a thriving concert and recital tradition,

particularly at the turn of the century.

During his youth he attended Leeds Grammar School, a few years after the composer John Ireland, and passed his Associateship

Diploma of the Royal College of Organists in 1903. In 1904, he became an unattached member of Durham University, a connection

which apparently lasted until 1915-16, although there is little evidence of what work he completed; music degrees were

often taken through correspondence-type courses at this time.

It is only in May 1905 that Ernest began to make important connections after he was awarded a scholarship to the Royal College

of Music where he studied composition under Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. It was during his time at the RCM that he became a

member of the ‘Beloved Vagabonds’, an exclusive musical and social club of influential young musical figures including the composer

Frank Bridge and the musicologist Marion Scott, who later became well known for her important role in the life of Ivor Gurney.

Ernest’s membership of this club seems to have had significant effect on the development of the composer, and the term ‘vagabond’

in particular seems to have been a favourite of his, perhaps surprising given his background (his brother followed his father into

the church and was noted as being particularly "feared", although by whom it is not clear).

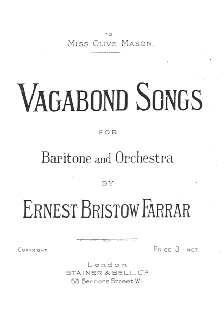

We find, for example, that Farrar names himself only ‘vagabond’ on the manuscript of his choral setting

of Shakespeare’s ‘It was a lover and his lass’, now deposited in the Bodleian Library, almost suggesting that he intended the name

as a sort of alternative moniker. His most significant song collection is probably the Vagabond Songs for baritone and

orchestra from 1913.

In keeping with this carefree, outdoor-influenced spirit, we also find works such as his 1909 First Orchestral

Rhapsody ‘The Open Road’, inspired by the poem by Walt Whitman, whose poetry he also based his later choral suite Out of Doors on.

"The Open Road" was also the name of an influential and much-reprinted 1899 poetry anthology compiled by E.V. Lucas

which features some of the poems Farrar was to set to music; he was to set Lucas's short poem "Brittany" in one of his more

well-known songs.

During his time at the RCM, as documented by Pamela Blevins in her biography of Marion Scott and Ivor Gurney, Ernest had a

relationship with the musicologist and violinist Marion M. Scott, who was nine years his senior.

This relationship appears to have been ongoing when Farrar left the College

in 1909 to take up a six-month post as organist at All Saints English Church in Dresden. In 1909 he was offered position of organist

at St. Hilda’s Church, South Shields, which he held from March 1910 to August 1912, where he was allegedly paid less than the caretaker.

It was at this time that Ralph Vaughan Williams sent his oft-quoted letter to Farrar:

I suppose I must congratulate you on your appointment – I certainly congratulate them – but it’s a beastly job being organist and unless one is very careful lowers one’s moral tone (not to speak of one’s musical) horribly.

Vaughan Williams may have been more right than he knew. During his time in South Shields, Farrar met and was engaged to Olive Mason,

the daughter of a chemist and a parishoner at the church.

However, Farrar became engaged seemingly without informing Marion Scott, who only found out on the night when she had

travelled to South Shields to perform the as yet-incomplete Celtic Suite for Violin and Piano Ernest had written for her.

Scott was devastated by this news; one can only assume the concert was an awkward affair. She never spoke to him again.

However, Farrar’s deception did have an unexpected side effect in that it brought Scott closer to Ivor Gurney, another young student at the RCM

for whom she was to play an important role in his welfare following the war and in the subsequenty preservation of Gurney's unpublished poetry and music.

Scott was devastated by this news; one can only assume the concert was an awkward affair. She never spoke to him again.

However, Farrar’s deception did have an unexpected side effect in that it brought Scott closer to Ivor Gurney, another young student at the RCM

for whom she was to play an important role in his welfare following the war and in the subsequenty preservation of Gurney's unpublished poetry and music.

Ernest married Olive Mason at South Shields in 1912, with the future organist of Westminster Abbey, Ernest Bullock, as his best man. Olive, incidentally,

was a great friend of the author Elinor Brent-Dyer, and readers of the Chalet School series may be familiar with Ernest Farrar's

name through repeated mentions of his song "Brittany" in those books.

Ernest gained a slightly more prestigious appointment to become organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Harrogate

in September 1912. To suppliment his meagre income, he advertised for pupils and became the teacher of

Harry Gill and H.P. Dixon in 1913, and most notably of Gerald Finzi in 1914.

The warm pedagogical relationship between Farrar and the aspirant composer Gerald Finzi is well documented. Farrar pointedly advised Finzi's mother

that there was little chance of his making money by composition unless one had 'private means' (possibly based on his own experiences to date).

However, Finzi was a regular visitor to Ernest's house in Hollins Road, Harrogate, and although Ernest apparently despaired of his

pupil's lack of focus, he encouraged his pupil by attending concerts with him and taking him to see C.V. Stanford in London with a view to

the young composer obtaining a scholarship there (although Finzi was ultimately unsuccessful at his assessment).

Ernest also became heavily involved in the thriving musical scene in Harrogate. He conducted the Harrogate Orchestral Society

and was involved with the Harrogate Municipal Orchestra through his friendship with the flamboyant conductor Julian Clifford,

who performed a number of his premieres, including the now-lost Orchestral Rhapsody No.2 ‘Lavengro’ in 1913, the extended orchestral fantasy

The Forsaken Merman in 1914 and the Variations on an Old British Sea Song on Ernest's 30th birthday in 1915.

Also during this period, Ernest wrote a large body of his smaller compositions, including the highly regarded choral part-song

Margaritae Sorori (‘The late lark’), a setting of W.E. Henley, the score of which proudly declares that it won second prize

in the “Mrs Sunderland Competition” in Huddersfield.

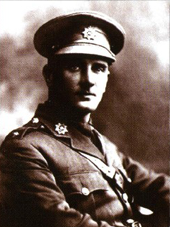

Farrar enlisted in the Grenadier Guards in 1915, and after a number of periods away from Harrogate training, he gained a commission

as 2nd Lieutenant in February 1918, apparently at the suggestion of Stanford and Vaughan Williams. During this period, his number

of compositions understandably dwindled, although his last major orchestral piece, the Heroic Elegy (For Soldiers) also dates

from 1918, which he personally conducted back in Harrogate on the 3rd of July 1918.

Farrar was summoned to France on the 6th of September, where he briefly befriended the playwright and later broadcaster J.B. Priestley.

Ernest was killed by machine gun-fire at the Battle of Ephey Ronssoy on the 18th of September, after two days at the Front.

His Musical Times obituary wrote that ‘He was a musician of the highest ideals, and was devoted to the art he served so faithfully.’

Stanford, writing in the Durham University Journal wrote:

Farrar was one of my most loyal and devoted pupils. He was very shy, but full of poetry, and I always thought very high things of him as a composer, and lamented his loss both personally and artistically.

Stanford personally attempted to bring his pupil’s music to wider attention and many of Farrar’s organ and vocal works were

published posthumously during the 1920s, However, following Stanford’s death, Farrar’s music saw a decline in popularity,

with the composer’s Edwardian idiom out of place in a post-war, urbane music scene. Many of his scores became mislaid and

his primary publisher, Stainer & Bell, did not keep copies of many works.

Legacy

Professor Stephen Banfield has noted that compared to contemporaries, Farrar’s death went almost unnoticed. Presumably,

by 1918 a certain inevitable fatigue must have set in when so many men had already been lost.

By taking a position in the North of England, Farrar had become isolated from his RCM contemporaries, many of whom gravitated towards London, Oxbridge

or Severn valley locales. While Farrar may have dedicated his English Pastoral Impressions to Ralph Vaughan Williams

and shared warm correspondence with him, he was not as close as, say, George Butterworth

was to the figurehead of this musical generation.

In fact, it was Farrar's tutor at the RCM who displayed the most regret, Ernest having been heavily influenced by Stanford's late Victorian style, with

Stanford's obituary in the Durham University Journal being complimentary of his abilities:

recognised as one of the most promising of the young British composers, and had he lived would have undoubtedly made a great name.

Of course, these obituaries were unlikely to be critical of their subject, but other evidence suggests that Farrar must have been

appreciated. Notably, two of his major orchestral works, the English Pastoral Impressions and the Three Spiritual Studies,

were published posthumously by the Carnegie Collection of British Music in 1924 and 1925 respectively.

Each year Carnegie Trustees would choose between one and six works which they felt constituted ‘the most valuable contributions to the

art of music’, which implies that both pieces would have, in their time, been highly regarded. Indeed, reporting on the publication,

the South Shields Gazette commented that the English Pastoral Impressions were ‘the subject of special commendation by the adjudicators’.

This also suggests, given his death in 1918, that he was advocated by another member of the musical fraternity, perhaps Stanford himself.

During this time Ernest's parents set up the Farrar prize for composition at the RCM, which included luminaries such as

Benjamin Britten amongst its recipients.

Gerald Finzi enquired to Farrar’s widow, Olive, on a number of occasions about his manuscripts, asking whether she would

bequeath Farrar’s manuscripts to either the Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society or the County Durham or

Newcastle Public Libraries, declaring:

when the history of those years is considered by future musical scholars, it may well be that his name will come up from the underground river.

Later, in 1953 Finzi asked Ernest Bullock, the director of the RCM and Farrar’s best man to house the manuscripts there.

However, this appears to have not happened and they remained in the possession of Farrar’s family.

It was only following an intervention by Adrian Officer in the 1980s that his manuscripts were deposited in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

A number of his works are now missing, most significantly his Orchestral Rhapsody No.2 ‘Lavengro’.

Adrian Officer informed me that he had made all efforts to locate the score during his research in the 1980s. However,

following Julian Clifford's premature death aged 44 in 1921, the Harrogate Municipal Orchestra went into terminal

decline and much of the music owned by the Orchestra was thrown out following the orchestra’s disbandment

in 1930. This is probably when the manuscript of Lavengro was destroyed, along with the

majority of Julian Clifford's music, including Lights Out.

For the 1997 Chandos recording of Farrar’s orchestral works, the RVW Trust funded the creation of new performing material from the manuscripts

for all of Farrar's works except the English Pastoral Impressions. In addition, the full scores of four works for voice and orchestra

(The Blessed Damozel, Out of Doors, Vagabond Songs and Summer) are lost, and now only survive as piano reductions.

The Blessed Damozel was re-orchestrated and performed in 1985 by Rodney Newton.

©2013 Robert Weedon

Back to the Farrar navigation page

Bibliography

This biography is based on part of a conference paper I presented at

The First World War: Literature, Music and Memory

held at King's College Cambridge, July 2009, in turn based on a longer dissertation ("Up from the Underground River")

supervised by Dr Bethany Lowe of Newcastle University. This was greatly aided by the late

Mr Adrian Officer of Northumberland, who allowed me to view copies of Farrar's original manuscripts and gave me access to some of the

research materials for his 1985 article on Farrar.

Anon., ‘Obituary: Ernest Bristow Farrar’ in London: The Musical Times, Vol. 59, No. 909. (Nov. 1, 1918), 503.

Anon., ‘A Posthumous Honour’ in The Shields Gazette, 2nd June 1920, 2.

Anon., ‘Oxford Puts a Shields Man with the Greats’ in The Shields Gazette, July 25th 1984, 3.

Anon., St. Hilda’s Parish Record (South Shields: 1910-13).

Anon., Special collections: The Carnegie Collection of British Music at King’s College, University of London.

Bainton, Edgar, ‘Some British Composers: Ernest B. Farrar’ (Publication unknown: scrapbook of Ernest Farrar, c.1913).

Banfield, Stephen, ‘Ernest Bristow Farrar’ in Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 26 September, 2007).

Banfield, Stephen, Gerald Finzi: an English Composer (London: Faber & Faber, 1997).

Banfield, Stephen, Sensibility and English Song (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Benoliel, Bernard, Ernest Farrar: Orchestral Works (Colchester: Chandos Records, Chan 9586, 1997).

Blevins, Pamela, Ivor Gurney and Marion Scott: Song of Pain and Beauty (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2008).

Child, William, ‘New Music: Songs’ in The Musical Times, Vol. 61, No. 926, (Apr. 1, 1920), 265-266

C.W, ‘New Music’ in London: The Musical Times, Vol. 62, No. 938, (Apr. 1, 1921), 265.

Dibble, Jeremy, Charles Villiers Stanford: Man and Musician (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.)

Foreman, Lewis, ‘The Broadheath Singers and the Farrar Centenary’ in Tempo, New Series, No. 155 (Dec., 1985), 38.

Godfrey, Dan, Music and Memories (London: Hutchinson & Co, 1924).

McVeigh, Diana, Gerald Finzi: His Life and Music (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press 2005).

Officer, Adrian, ‘Ernest Bristow Farrar’ in British Music Society Journal, (Volume 7, 1985). 1–10.

Officer, Adrian, ‘Who Was Ernest Farrar?’ in The Lads in Their Hundreds (Recital programme, 1984), 7-12.

Officer, Adrian, ‘Harrogate and Ernest Farrar’ in Jordan, Rolf, (ed.) The Clock of the Years: A Gerald and Joy Finzi Anthology (Lichfield: Chosen Press, 2007).

Scott, Marion, ‘Second Lieut. Ernest Bristow Farrar’ obituary, in Royal College of Music magazine (vol. 15, September 1918).

Stanford, Charles Villiers, Durham: Durham University Journal, New Series (December 1918), vol.22, no.1, 30.

Webster, Donald, ‘Ernest Bristow Farrar’ in Jordan, Rolf, (ed.) The Clock of the Years: A Gerald and Joy Finzi Anthology (Lichfield: Chosen Press, 2007).

Weedon, Robert, 'Up from the Underground River': A Study of Ernest Bristow Farrar, Dissertation, (University of Newcastle, 2008)