William Denis Browne - a biography

William Charles Denis Browne, known to friends as 'Denis' and 'Billy' to his family, was born

in Lynnwood, Leamington Spa, but with an Irish heritage from both of his parents.

He exhibited profound musical ability from a young age, having perfect pitch and a

seemingly intuitive talent at playing the organ. A recollection from his family tells

that he used to pester local organists to allow him to try

them out before he could even reach the pedals.

He attended Greyfriars School in Leamington (a photograph

of him at this prep school recently appeared in the Leamington Spa Courier). Having turned down a scholarship to Harrow School, he attended Rugby School from 1903 where he became friends with Rupert Brooke, who was in the year above.

An oft-recounted story tells that Brooke, on being asked for a poem to set to music was miffed by the request and wrote a dirge

called 'A song in praise of Cremation written to my lady on Easter Day'.

The composer's tongue-in-cheek response to the text, now lost, cemented their friendship.

He attended Greyfriars School in Leamington (a photograph

of him at this prep school recently appeared in the Leamington Spa Courier). Having turned down a scholarship to Harrow School, he attended Rugby School from 1903 where he became friends with Rupert Brooke, who was in the year above.

An oft-recounted story tells that Brooke, on being asked for a poem to set to music was miffed by the request and wrote a dirge

called 'A song in praise of Cremation written to my lady on Easter Day'.

The composer's tongue-in-cheek response to the text, now lost, cemented their friendship.

In 1907 he went up to Clare College Cambridge where he was the organ scholar and during which time

he arranged for the installation of a brand new organ which remains the instrument in the chapel today.

As is common with nearly all of the War Composers, he largely forewent his academic studies

for the pursuit of music (he was supposed to be reading Classics),

becoming perhaps the best known musician at the university; an

outstanding pianist and organist, he was still cited many years after his death

by Professor Edward Dent as the "cleverest of the Cambridge musicians" of the period in a group that

included Clive Carey, Arthur Bliss, Cecil Armstrong Gibbs and others (Dent Essays, 86).

He stayed on at Cambridge as organist at Clare for additional terms after his degree was complete, and

fully participated in the theatrical and musical life of the university. He was in the chorus of the

Cambridge Greek play The Wasps (1909) which famously featured music by the up-and-coming Ralph Vaughan Williams.

He was also in the cast of the Marlowe Dramatic Society performance of John Milton's masque Comus in 1908.

Denis Browne and Edward Dent were the arrangers of the incidental music, which was transcribed from

Elizabeth Fitzroger's Virginal Book, a book of Elizabethan keyboard music which at the time had not been widely studied.

The whole cast found themselves humming a short anonymous allmayne which later became the basis of

the 'ground' accompaniment of “To Gratiana Dancing and Singing”.

There are several surviving instances of the composer transcribing 16th and 17th century lute works from tablature into staff notation

in the Cambridge University Library (MS Add.5998)

which are dated circa 1908.

It may be that these were for this production, or perhaps just an academic exercise; they were certainly not published.

Either way, Denis Browne seems to have been interested in the music of this period, and it influences the Neo-Renaissance

sound world of his Elizabethan poetry settings in similar fashion to the post-WWI vocal works of Peter Warlock.

Influences and experiments

After leaving Cambridge, in common with many of the War Composers, the familiar conundrum of the music student

began to set in; having developed a passion for the arts, music and theatre at university and not wishing to

join one of the expected professions for a university graduate (his father intended him to join the Civil Service),

he left without a clear view of what he should do to earn him a living.

Throughout his twenties he appears to have been trying his hand at various music-related careers as a recitalist,

teacher, critic and composer without appearing to know which he was best suited to.

He took a post teaching at Repton School in Derbyshire in 1912, which he evidently disliked, and continued to work as a recitalist.

However, the possibility of being a full-time concert performer had stalled following a trip to Berlin to study with Ferrucio Busoni,

where overzealous keyboard practice caused a form of neuritis which could have led to permanent paralysis of his hands.

This led him to leave his job at Repton and focus energies closer to London where his career would now be described as a "freelancer".

He became musical director at Guy's Hospital, London in 1913, also deputising for Gustav Holst as a composition tutor in the music

department of Morley College, the adult education college. Meanwhile, he also tried his hand at music criticism,

writing for the The Blue Review, The Musical Times, The Times and The Daily Telegraph amongst other publications.

Several examples of his music criticism survive, which vary from insightful, perhaps even slightly waspish

Blue Review pieces which offer a glimpse into British music in the pre-war period

to the more academic, but somewhat turgid "Modern Harmonic Tendancies" in Musical Times.

Through his critical career, Denis Browne gained exposure to premieres of some of the most important new works coming from the

Continent and Russia; he was one of the first British composers to fully appreciate the Modernist movement, and argued persuasively

in support of new works such as Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (1913) when they were still considered controversial.

Although as a composer, he never fully had an opportunity to compose any quantity of music in this idiom,

The Comic Spirit does display prototypical elements of Stravinksy's earlier ballet scores,

and he performed the London premiere of Anton Berg's Piano Sonata in May 1914.

All of this suggests that Denis Browne was more atune to the European musical zeitgeist than the

19th century German-influenced sound heard in early works by composers taught at the Royal College of Music,

or the influence of the English folksong movement that had been gaining currency with fellow composers

looking for a new-old "English" sound. It is notable that Arthur Bliss also reacted against the Germanic 19th century sound

with his quirky post-war works; Dent, whose correspondence gives a picture of a man vehemently against the Brahmsian school of composition,

was perhaps a stronger influence on the taste of the Cambridge composers than has been acknowledged.

Denis Browne also gave private recitals as an accompanist to friends forging singing careers such as Steuart [sic] Wilson,

even performing a recital at Downing Street, for example. Vaughan Williams, who seems to have known every one of the War Composers at some point,

asked Denis Browne to give a private first run-through of his ballad opera Hugh the Drover at his house in June 1914,

with Wilson as the tenor soloist (Denis Browne had also performed an early run-through of On Wenlock Edge while still a student in 1909).

Shortly before joining the Navy, Denis Browne was also part of the group of RVW's friends working to recreate from parts

the score of A London Symphony, which had been misplaced in Germany at the outbreak of the war

(one therefore assumes Denis Browne also knew George Butterworth, who is mostly credited for this work today).

The Georgians

Through Brooke, at a performance of Stravinsky's Petrushka, Denis Browne had been introduced to Edward Marsh,

the influential civil servant who also edited the five volumes of Georgian Poetry from 1912 and 1922,

anthologies of British contemporary lyrical verse ("Georgian" referring to George V,

not the earlier historical period for which it is now usually applied).

Denis Browne became more acquainted with this literary set, especially the Cotswold-based "Dymock Poets"

while Brooke travelled in 1913 and 1914.

Denis Browne must have been taken with the "Georgian" label, for he also began to assess contemporary British

music within this framework; his first article for the short-lived Blue Review (May 1913) was headed

"Georgian Music",

where he discusses the merits and flaws of fellow composers such as Cyril Scott, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and Henry Balfour Gardiner.

One assumes his setting of Walter de la Mere's "Arabia" (included in the first Georgian Poetry anthology)

was as a result of his acquantance with the poet. Other names featured in this anthology included John Masefield (whose prose drama

Tragedy of Nan was the counterpart to the Bristol performances of The Comic Spirit in 1914 (Lancaster, 54)

and Wilfred Wilson Gibson who commemorated both Brooke and Browne in his collection Friends (1916).

World War I

When not editing poetry anthologies, Marsh was the Private Secretary to Winston Churchill (then First Lord of the Admiralty),

and on the outbreak of war Brooke pushed to obtain a commission in the Navy. However, he then refused to go unless Denis Browne was also commissioned.

Thus, by September 1914 they were both temporary Sub-Lieutenants in the Royal Naval Division, joining the Anson Battalion of the 2nd Naval Brigade.

Evidently, organisation in the early part of the war was poor: they sailed on the Antwerp Expedition in October 1914,

but having already encountered numerous delays, that campaign was already virtually lost before they arrived

so they were transferred to the newly-formed Hood Battalion

(all of the RND batallions were named after famous naval commanders, in this case Samuel Hood). The two friends

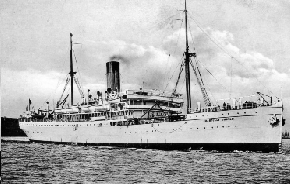

assembled on the Grantully Castle, a liner requisitioned at the start of the war.

It sailed from Avonmouth at the end of February 1915 to the Dardanelles in the eastern Mediterranean.

Amongst the officers on board were an extraordinary group of like-minded poets, musicians and sons of the "great and good".

Another composer acquaintance, the Australian Frederick Kelly, was also on board and from correspondence early in the voyage,

the two apparently spent time playing piano duets and arranging music for the Hood band.

It seems between bouts of dysentery that it was quite a jolly outing. Then Brooke died.

It sailed from Avonmouth at the end of February 1915 to the Dardanelles in the eastern Mediterranean.

Amongst the officers on board were an extraordinary group of like-minded poets, musicians and sons of the "great and good".

Another composer acquaintance, the Australian Frederick Kelly, was also on board and from correspondence early in the voyage,

the two apparently spent time playing piano duets and arranging music for the Hood band.

It seems between bouts of dysentery that it was quite a jolly outing. Then Brooke died.

The shock of losing his best friend must have taken its toll on Denis Browne, and the reality of what they were getting into

cast a shadow which never quite lifted. Denis Browne's correspondence understandably becomes more fatalistic.

The ship dropped them off to fight alongside the assembled ANZAC forces at Gallipoli.

It was there in June 1915 that Denis Browne, having already been hospitalised with a neck injury from a sniper earlier in May,

made an ill-judged decision to return to fight while still unfit. He fought in the disastrous

Third Battle of Krithia.

He was badly wounded, and his unit forced to retreat. His body was not recovered.

Legacy

Before and beyond Cambridge it is Denis Browne's evident talent for composition that he is remembered for,

even though it is unlikely that he would have thought of himself in this way.

Indeed, it can be said that he was only just hitting his stride as a composer with the composition of 'To Gratiania'

in 1913 and his work on The Comic Spirit in 1914.

Regrettably his talents as a composer can now only be judged on the contents of one box of surviving pieces

held by the archive of Clare College Cambridge, plus one other autograph manuscript held by the British Library,

all of which offer a tantalising glimpse of a lost composer.

On learning of Denis Browne’s death at Gallipoli in 1915, Edward Dent, perturbed by the outpouring of public

sentimentality following Rupert Brooke’s demise gathered up Denis Browne’s manuscripts, sifted through them and

burnt many at the composer’s instruction to destroy anything that did not represent ‘Denis Browne at his best’.

In a distressing letter to Dent dating from either the day before or even the day of his death Denis Browne advises:

It’s all rubbish except Gratiana, (perhaps) Salathiel Pavey, & the Comic Spirit...Everything else except what I’ve mentioned must be destroyed." (King’s College Archive Centre PP/EJD 4/61)

It’s easy to think of Dent as a literalist who is often painted by biographers as having destroyed the legacy of a young composer.

However, he could have gone a lot further and while he squirreled Denis Browne's finest songs away until after the war (for perhaps good reason),

if the composer's wishes had been fully realised, we would not even have works such as 'Diaphenia' or his Two Dances for Small Orchestra.

As it stands, at least six of his songs have been published and anthologised, a piano Intermezzo is also available in print, and

the majority of his songs have been recorded and are available on CD.

So what of what was lost? Given that opinions of his first two published songs of Tennyson are generally negative

(indeed the composer himself apparently regretted their publication), one can perhaps understand Denis Browne's

attitude that only his best work should outlive him.

Thus, we know that the songs written while at school, his "juvenilia", such as the aforementioned "Ode on Cremation" are gone, as

is another song setting of Brooke's words. The quantity of unfinished material left at his death is unknown.

Regrettably, of The Comic Spirit, the second manuscript books of both of the piano duet versions have been mislaid,

and the orchestrated version was not completed, thus rendering the work incomplete. According to Dr Philip Lancaster, whose article

in British Music offers a full account of the circumstances of the work's performance, a copy of a full score which

Edward Dent was using to try and persuade Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes to perform it has also disappeared (Lancaster, 71).

A conjectural completion has been written of both the orchestral and piano duet versions, however,

and the work was re-premiered with dancers from the Central School of Ballet at Clare College in November 2014.

The correspondence-based biography of Dent, Duet for Two Voices has a photograph of Robert Maltby dancing "the part of Puck in Denis Browne's

Spirit of the Future, 1913" (p.75) in a costume that unfortunately in silhouette looks rather like a large gnome.

However, the reference to the Spirit of the Future is both interesting and confusing; it is seemingly the only reference to a ballet

of this name dating from 1913; "Puck" obviously implies a Shakespeare connection, but the second subject theme

of The Comic Spirit is labelled in the manuscript as "Dance of the Spirit of the Future". Given Denis Browne's track record of

reusing part of his earlier Dances in this ballet, perhaps we can make a reasonable assumption that this was either a prototype of

The Comic Spirit or another ballet composition whose music made an appearance in his later work.

The correspondence-based biography of Dent, Duet for Two Voices has a photograph of Robert Maltby dancing "the part of Puck in Denis Browne's

Spirit of the Future, 1913" (p.75) in a costume that unfortunately in silhouette looks rather like a large gnome.

However, the reference to the Spirit of the Future is both interesting and confusing; it is seemingly the only reference to a ballet

of this name dating from 1913; "Puck" obviously implies a Shakespeare connection, but the second subject theme

of The Comic Spirit is labelled in the manuscript as "Dance of the Spirit of the Future". Given Denis Browne's track record of

reusing part of his earlier Dances in this ballet, perhaps we can make a reasonable assumption that this was either a prototype of

The Comic Spirit or another ballet composition whose music made an appearance in his later work.

Also tantalising is a reference to The Enchanted Night, an entertainment apparently co-written by Edward Dent and Denis Browne

(Duet for Two Voices, 84). Like the Comic Spirit, The Enchanted Night featured

a scenario by Violet Pearn. The programme from the production mentions the involvement of Clive Carey, Denis Browne, Robert Crighton and others

(King’s College Archive Centre EJD/7/5/1).

One can imagine it being an interesting piece, but like so much of this composer's work, one can only guess "what if?"

Robert Weedon, February 2014

Bibliography

I would like to thank Mr Robert Athol, the Edgar Bowring Archivist at Clare College Cambridge for his assistance

in a related project about Denis Browne looking at Cambridgeshire composers in WWI, and to Mr Nick Peacey for providing some

of the information included in this article. The following reference works have been consulted, but my apologies if

any books or articles have been missed off; I believe Mr Hugh Taylor was responsible for much of the preliminary biographical

research on Denis Browne in his biographical essay and review of works available at the Clare Archive.

Banfield, Stephen, Sensibility and English Song (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985)

Blevins, Pamela, William Denis Browne, Musicweb International 2000

Brooke, Rupert, Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke with a Memoir (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1924)

Browne, W Denis, various articles in The Blue Review, Vol 1, Issues 1-3 (1913), available online at the Brown/Tulsa Universities Modernist Journals Project

Carey, Clive & Dent, Edward J, Duet for Two Voices (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979)

Davies, Rhian, "William Charles Denis Browne" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Dent, Edward J, "Cecil Armstrong Gibbs" in Selected Essays, ed. Hugh Taylor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979, reprinted 2009)

Dent, Edward J, "Death of Denis Browne" in The Musical Times, Vol. 56, No. 869 (Jul. 1, 1915), pp. 407-408

Hold, Trevor, Parry to Finzi: Twenty English Song-Composer (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2005)

Lancaster, Philip, 'Waking Up England': W Denis Browne and The Comic Spirit in British Music Society Journal, Vol. 26 (2004), pp. 47-74

Taylor, Hugh, 'The life and work of W. Denis Browne', unpublished academic work dated 1973 available at Clare College Archive.

Back to the Denis Browne navigation page